The period after the fall of the Roman Empire in A.D. 476 and before the Renaissance in the 14th century is commonly referred to as the Middle Ages or medieval period.

Now divided into individual nation states, the people of Europe turned to the Catholic Church to unify them. The thousand-plus years that make up the Middle Ages encompassed numerous different periods, ranging from the Byzantine and Anglo-Saxon to the Romanesque and Gothic, but the Church was nevertheless an effective unifier both culturally and artistically.

Although the name “Middle Ages” comes from the Renaissance period’s assumption that little of scientific or artistic significance was achieved during this time, contemporary historians maintain “that the era was as complex and vibrant as any other.” In fact, medieval communities showed their devotion to the Church by building impressive cathedrals, monasteries, and other religious structures, for which they turned to desirable materials, such as ceramic tile.

Medieval Tile History and Purpose

In his book “5000 Years of Tiles,” Hans van Lemmen explains that ceramic tile fell out of use in northern Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire, when architecture returned to timber frames, thatched roofs, beaten earth floors, and other less sophisticated construction techniques. Although the ceramic tile industry in Moorish Spain was already well developed, most of Europe didn’t begin producing tile again until the second half of the 12th century, with the first developments occurring in Germany, France, and Britain.

Ceramic tile was preferred over marble and stone because it could be locally sourced and produced and was therefore more affordable. Additionally, ceramic tile was easier to work with in a variety of spaces and had more aesthetic options.

Perhaps most important, however, was the fact that “[b]eing able to afford ceramic tiles was a clear outward sign of wealth, prestige and power,” even if tile was more affordable than marble and stone.

European citizens had to tithe 10% of their yearly income to the Church during the medieval period and the Church was largely tax-exempt. “1000 Tiles: Ten Centuries of Decorative Ceramics” (edited by Gordon Lang) suggests that ceramic tile not only allowed the Church to flaunt the money amassed through this system, but also to reinforce its position of supremacy. Nobleman made wealthy through the feudalism of the time also used ceramic tile to exemplify their position.

Because of the expertise and labor required for producing and installing ceramic tile during the medieval period, tile originally only adorned religious structures such as abbeys and parish churches, royal palaces, and the homes of the most wealthy and important citizens. However, this trend changed with the bubonic plague known as the “Black Death” (1347-1350), which killed 30% of Europe’s population.

The decimation of London’s workforce led to a demand for tile craftsmen and more efficient production during the late 14th and 15th centuries, according to Joe O’Brien of Fordham University. Kilns that had previously belonged only to churches and the gentry began to appear on the outskirts of towns, giving rise to a new tile industry that offered access and affordability of tiles to the rising merchant classes.

Medieval Tile Makers and Their Tools

Tile manufacturers were faced with limited resources, as they needed sufficient water, sand, and clay to create the tile, wood to fire the kilns, and lime deposits to make mortar. Despite these challenges, Van Lemmen notes that medieval tile makers experienced growing success because they were able to skilfully manufacture ceramic tiles with simple tools, materials, and kilns while also meeting “certain conditions relating to production methods, forms of transportation, market demands, and use of skilled and unskilled labour in order to function effectively.”

Tile making was seasonal during the medieval period. Manufacturers would dig the clay in the winter and allow it to “weather” until the spring or summer brought drier conditions, when they would make and fire the tiles. Different types of clay with varying levels of suitability could be found in different areas and tile manufacturers had to take this into account, as well. Although different tile decoration techniques required different preparation, the basic manufacturing process involved preparing and shaping the clay, glazing, and firing.

Made of bricks, waste tiles, and clay, medieval kilns consisted of two or more rectangular furnace chambers constructed below ground and one rectangular chamber on top of them, where the firing took place. While proper firing required temperatures of 1,000 degrees Celsius, manufacturers during this era had no devices to measure temperature and had to rely on their experience alone. This guesswork meant that no two batches of tile were exactly the same.

Tilers originally worked for commissions according to “1000 Tiles,” but were later given bread and butter and a daily wage. Van Lemmen suggests that they likely traveled from one construction site to the next at the beginning of the 13th century, working on-site to avoid having to transport the heavy tiles. Once a tile flooring job was complete, the kiln would often remain on-site to create roof tiles for the building or tiles for other clients nearby.

As tile manufacturing became more commercial in the 14th century, tile makers began to work more in designated production centers and were paid according to their production, such as per thousand tiles produced.

Medieval Tile Decoration

The medieval period encompassed many different artistic periods and styles, and medieval tile is equally diverse.

Ceramic tile in religious buildings often depicted important Christian scenes or symbols, such as the popular fleur de lis, which was associated with the Virgin Mary’s purity. Even tile that was devoid of religious significance, such as mosaic tile, contributed to the religious buildings’ spiritual majesty, as did stained glass and other decorations.

Ceramic tile in secular buildings featured geometric designs, mosaics, and prestigious symbols such as family crests. Family crests could also be found in monasteries and churches, where they portrayed the family’s patronage and, in the community’s eyes, piety.

Types of Medieval Tile

Relief Tiles: High-Relief Tiles, Counter-Relief Tiles, and Line-Impressed Tiles

According to “5000 Years of Tiles,” the Anglo Saxons began creating the earliest medieval ceramic tile in the late 10th or early 11th century by pressing stamps into clay before firing, a technique now known as “relief” (from the Latin “relevare,” meaning “to raise”). Excavations across England have shown that relief tiles were used in churches, and examination of the backs of the tiles suggests that they served as both floor tiles and wall tiles or risers.

Relief tiles were manufactured throughout northern Europe starting in the second half of the 12th century, and were particularly popular in Switzerland and Germany. Techniques varied across locations and changed over the years. For example, manufacturers might use multiple small stamps, or one larger stamp.

Three types of relief tiles existed in the Middle Ages:

- High-relief tiles: High-relief tiles feature a raised design and sunken backdrop (made up of the surface of the tile).

- Counter-relief tiles: The opposite of high-relief tiles, counter-relief tiles feature sunken designs within the background.

- Line-impressed tiles: Line-impressed tiles feature a design of thin lines impressed into the surface.

After stamping the tiles and letting them dry, tile manufacturers would cover them with a glaze. For darker colors, they would apply the glaze directly to the tile, and for lighter colors, they would first apply a thin layer of white slip. Alternating dark and light tiles allowed for striking designs.

However, the most crucial element of relief tile design was the effect of shade and light, which drew attention to the raised or impressed pattern.

Mosaic Tiles

Mosaic tile was the second medieval tile technique to be developed according to “5000 Years of Tiles,” beginning in late 12th-century France and probably evolving from marble mosaic floors in southern Europe.

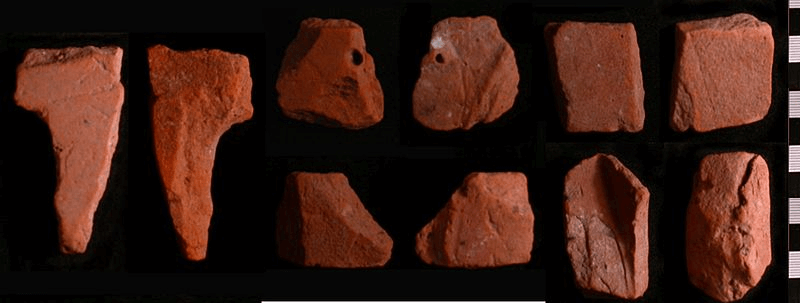

Deiniol Williams, a contemporary tile artisan, explains that medieval mosaic tiles were cut out of clay using templates in various shapes, allowed to dry, and then assembled to create a geometric pattern. Manufacturers would cut the tiles at a slight angle tapering inward, so that the surfaces would touch when the tiles were laid but the backsides would not. This technique made space for the mortar without allowing it to be seen.

Manufacturers created a range of dark and light colors that installers would then alternate to create unique tile patterns. The tiles themselves had little or no pattern, except for sometimes the larger centerpieces of the tile design.

Eventually, medieval mosaic tile techniques evolved to include complex geometric shapes, including large circular pavements. Because the tiles converged toward the center in circular pavements, careful measurements were necessary to ensure that everything fit together correctly. The experience and skill necessary for these applications are likely the reason why the technique was abandoned in the 13th century.

Inlaid Tiles

Inlaid tile (or two-color tile) was the most important type of medieval tile according to van Lemmen because the inlaying of two different colors of clay into each other created multicolor designs and allowed for the development of more complex ornamentation. “1000 Tiles” further explains that most inlaid tiles consisted of red clay with white inlay, although occasionally white clay with red inlay was used.

The inlaid tile manufacturing process involved multiple steps to mold the base tile and stamp it with a raised design that created an indented area in the clay base. The second color of clay was then poured into the indented area to complete the design before glazing and firing.

Manufacturers used the clearest glazes available, which changed the red and white clay to brown and yellow. The inlaid process created a finished tile that could have a sharp yellow design against the contrasting brown tile body. The design was sometimes complete on the single tile alone, and sometimes each tile made up part of a larger design involving multiple tiles.

Van Lemmen suggests that inlaid tile likely originated in France in the early 13th century, where it was widely used in abbeys, cathedrals, and secular residencies. From there, inlaid tile spread through traveling French tile makers and became popular in Britain, Ireland, and the Low Countries (the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg) through the 16th century.

Note: Inlaid tile would later regain popularity during the Gothic Revival period, at which point Victorians began calling it “encaustic tile” by mistake because they thought it looked like ancient Greek enameling. (“Encaustic” means “to burn” in Ancient Greek, and refers to an enameling technique that involves painting with beeswax-based paint before firing.) The term “encaustic” has been misused when referring to this type of tile ever since!

Tin-Glazed Tiles

Tin glazing was the most uncommon and smallest-scale tile technique to develop during the medieval period.

Tin-glazed tiles were covered with an opaque glaze made from adding tin oxide to lead glaze, which was likely originally used to cover up flaws in fired clay, according to the editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Tin oxide was rare and thus expensive during this time, and making the glaze required great skill. Additionally, tin-glazed tiles required two firings (one for the clay body and one for the glaze), lengthening the process and making it more costly.

Unlike lead glaze, tin glaze does not spread or run when it’s fired, so the pigments do not blur. This advantage was important, as tin-glazed tile was usually decorated with high-temperature colors. However, because the surface of the tile was so absorbent after the first firing, alterations were impossible with tin-glazed tiles.

Tin glazing spread to northern Europe in the 14th century through Moorish Spain and then Italy, and the tin-glazed tiles produced in the Netherlands and England would later be known as the still-famous “delftware.” Tin-glazed tile is known as “majolica” (or “maiolica”) in Italy and “faience” in France, Spain, Scandinavia, and Germany for the cities of Majorca, Spain and Faenza, Italy, where tin glazing was common and much admired.

Medieval Roof Tiles

Van Lemmen explains that ceramic roof tiles fell out of use after the dissolution of the Roman Empire (A.D. 476) and didn’t regain popularity until the 12th century, when they started to adorn royal palaces, abbeys, and other prestigious structures. Later in the medieval period, ceramic roof tiles also served to reduce the fire risk associated with thatched roofs.

To create ceramic roof tiles, medieval tile makers rolled out clay on a sanded table and used a template or wooden four-sided frame to cut out rectangular tiles. They would then alter the tile so that it could be applied to the roof, by creating either a hole at the top of the tile so that it could be hung with a nail or a flange on the back of the tile so that it could be hooked over the roof battens.

Special ceramic roof tiles also served to cover angles and joints. Ridge tiles, which sealed the gap between sloping roofs, sometimes doubled as decorations with ornamental crests and “finials” (pinnacle-like embellishments).

Medieval Tile Inspiration

Medieval tile lives on in countless medieval-inspired tile designs in homes and businesses around the world. Striking two-color tile designs and especially innovative dimensional examples are trending in contemporary tile production. Explore our Design Gallery for examples of modern medieval tile and inspiration for your home.