The Prophet Muhammad revealed the religion of Islam on the Arabian Peninsula in the early seventh century. In the centuries that followed, Islam spread elsewhere in the Middle East and then on to Asia, North Africa, and Southern Spain. Various Islamic empires existed for nearly 1,300 years, until the Ottoman Empire, the last of the Islamic empires, was dissolved at the end of World War I.

For a culture and religion that spread over so many centuries, areas, and empires, the unique identity of Islamic art is truly remarkable. Islam binds culturally and ethnically diverse groups of people, and its art follows suit, featuring intrinsically unifying characteristics. One of these characteristics is the preference for decorating all surfaces, especially with tile.

Most Islamic countries were using tile to decorate important buildings such as mosques, holy shrines, palaces, graves, and religious colleges by the ninth century. Today, decorative tiles are a tradition in virtually all Islamic countries, and the impact of Islamic tile is evident in its continued use in modern western applications.

Islamic Tile Decoration

The Met Museum explains that Islamic art is defined by the opposition to the depiction of human and animal forms. Islam holds that the ability to create living forms is unique to God, who is called “musawwir” or “maker of forms” in the Qur’an.

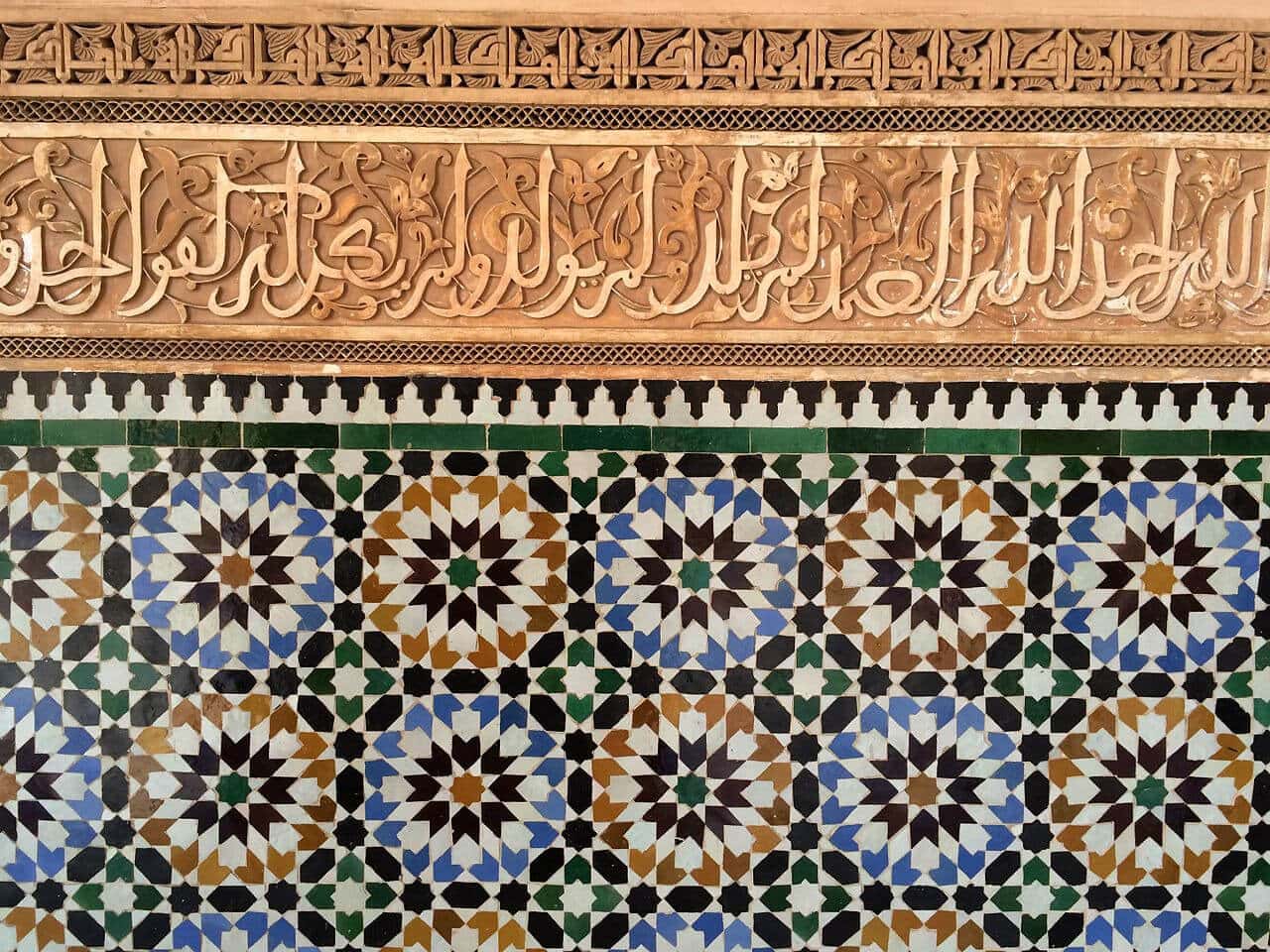

This aniconism forced Muslims to find different designs as a means for self-expression. As a result, many Islamic decorations feature stylized motifs and either interlacing patterns (such as geometric designs or arabesques) or calligraphy — or a combination.

Geometric Patterns

Geometric patterns are one of the most distinguishing features of Islamic tile and Islamic art as a whole according to the Met Museum, but they didn’t originate in Islamic culture. Islamic artists borrowed key elements of geometric patterns from the Greeks, Romans, and Sasanians, and then developed them into what would later become quintessentially Islamic designs. In his article “Geometric proportions: The underlying structure of design process for Islamic geometric patterns,” Loai M. Dabbour explains that Islamic geometric patterns draw heavily from mathematics and emphasize the importance of unity and order, as evidenced by God’s creation of the universe.

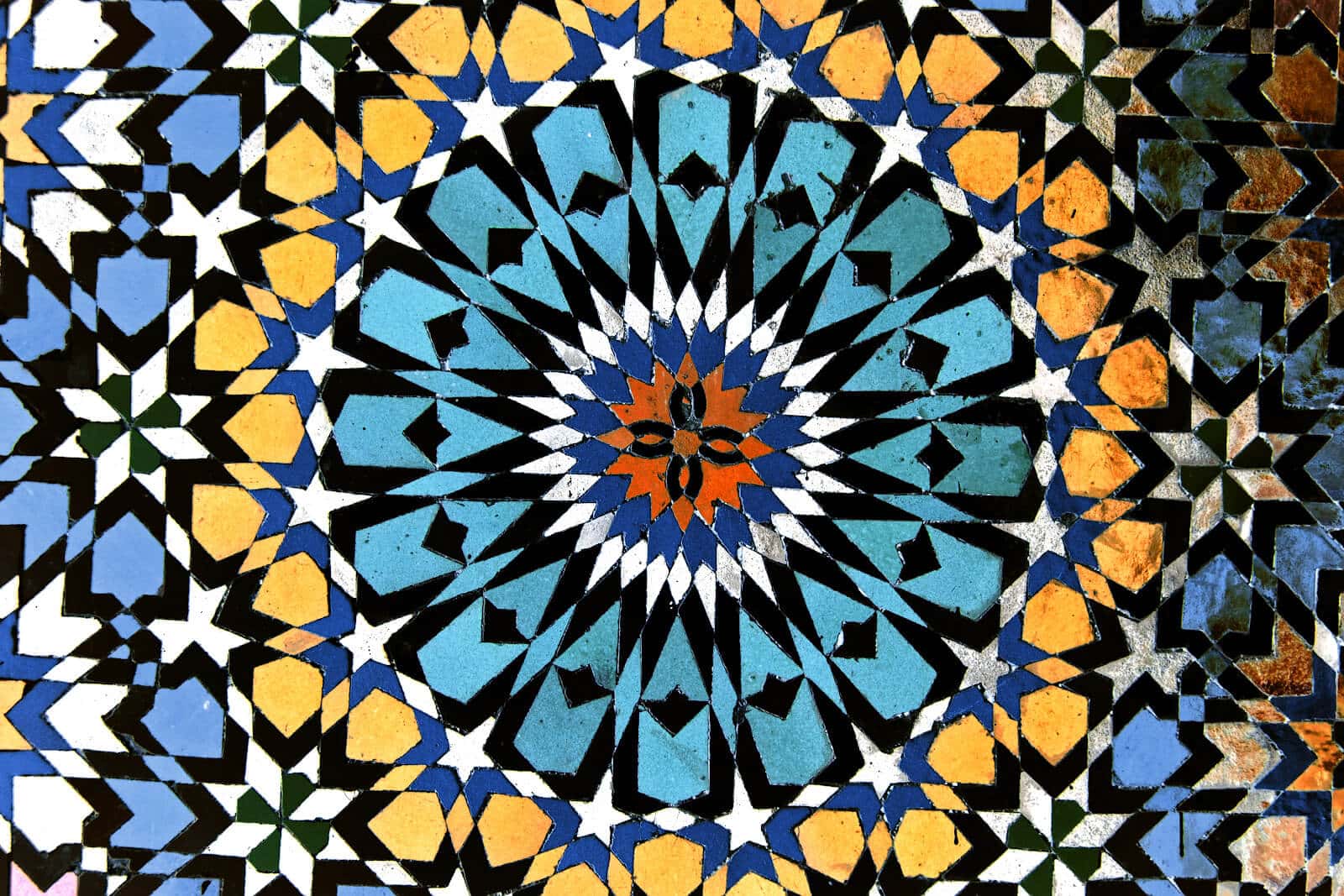

The geometric patterns in Islamic tile consist of simple shapes that are combined, interlaced, duplicated, and laid out in complex designs. Four basic shapes make up most Islamic tile designs:

- Circles

- Squares and other four-sided polygons

- Stars (or triangles and squares arranged in a circle)

- Multisided polygons

Islamic geometric tile designs aren’t restricted to these four shapes; it’s the repetition, combination, and arrangement of shapes that brings patterns to life in Islamic design.

Arabesques

The arabesque is the “epitome of Islamic art.”

–Rachida El Diwani, Professor of Comparative Literature, Alexandria University in Egypt

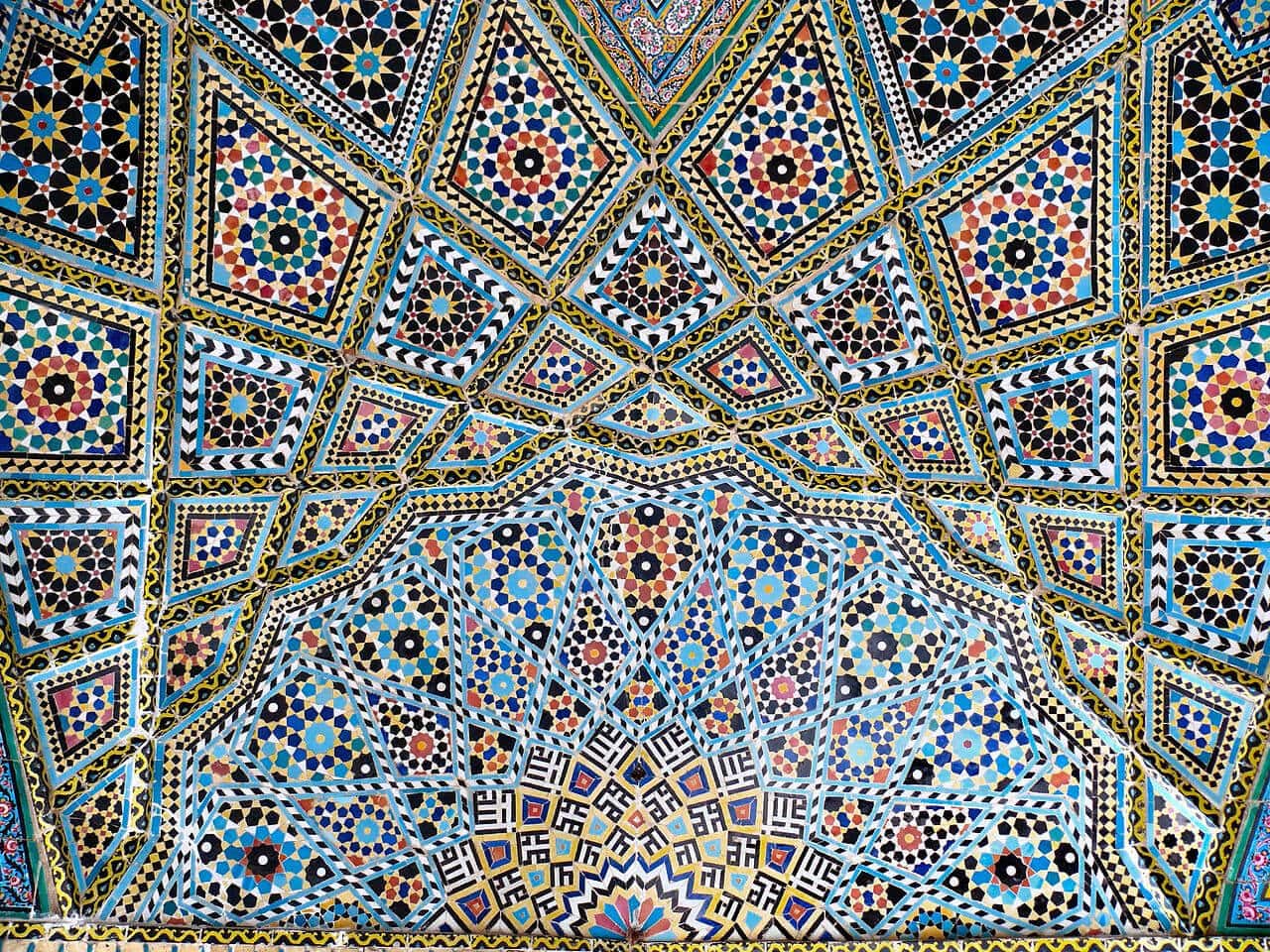

Rachida El Diwani explains that the arabesque design consists of vegetal designs borrowed from nature (flowers, tree leaves, vines, and so on) and geometric patterns in potentially limitless repetition, signifying the infinity of God and the impermanence of earthly objects.

Arabesques likely originated in Baghdad in the 10th century and were used in most Islamic architecture through the 14th century, according to Tasha Brandstatter from Classroom. As Islamic culture spread from South Asia to the Middle East and later to Spain, arabesque design went with it.

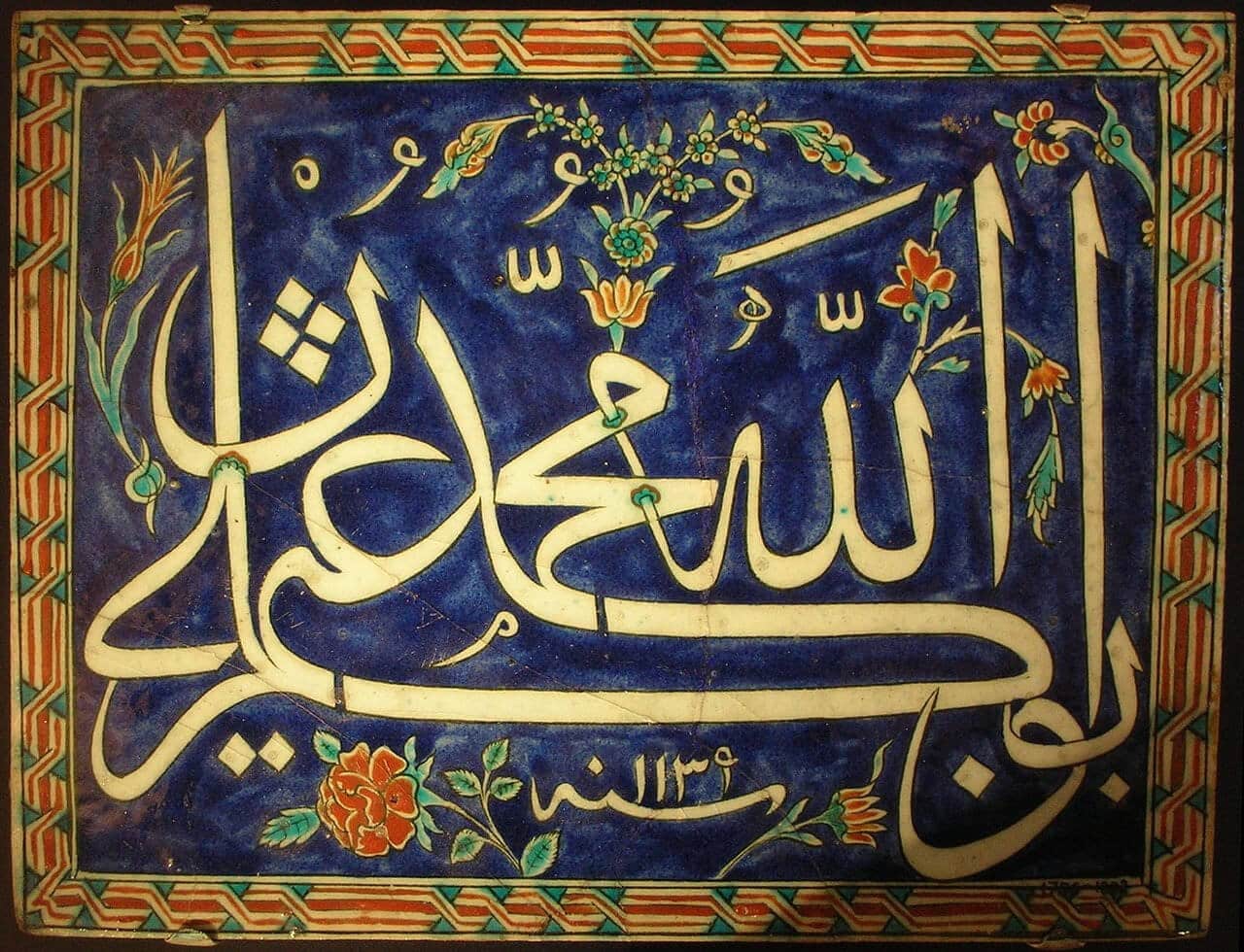

Calligraphy

The Victoria and Albert Museum reports that the Islamic culture has used calligraphy more widely than any other group, taking the written word from paper to all art forms, including tile and architecture. Arabic is significant to Muslims because it was the language used to reveal the Quran to the Prophet Muhammad in the seventh century. Arabic calligraphy seen in Islamic tile is often used to convey the message of the Quran, but Islamic tile calligraphy is also used to transmit other religious texts, praise for rulers, poems, and aphorisms.

As the Met Museum points out, Islamic tile calligraphy was not merely functional. Calligraphy had a strong aesthetic appeal as well, offering the possibility for limitless creativity. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Islamic Art explains that “[a]n entire word can give the impression of random brushstrokes, or a single letter can develop into a decorative knot.”

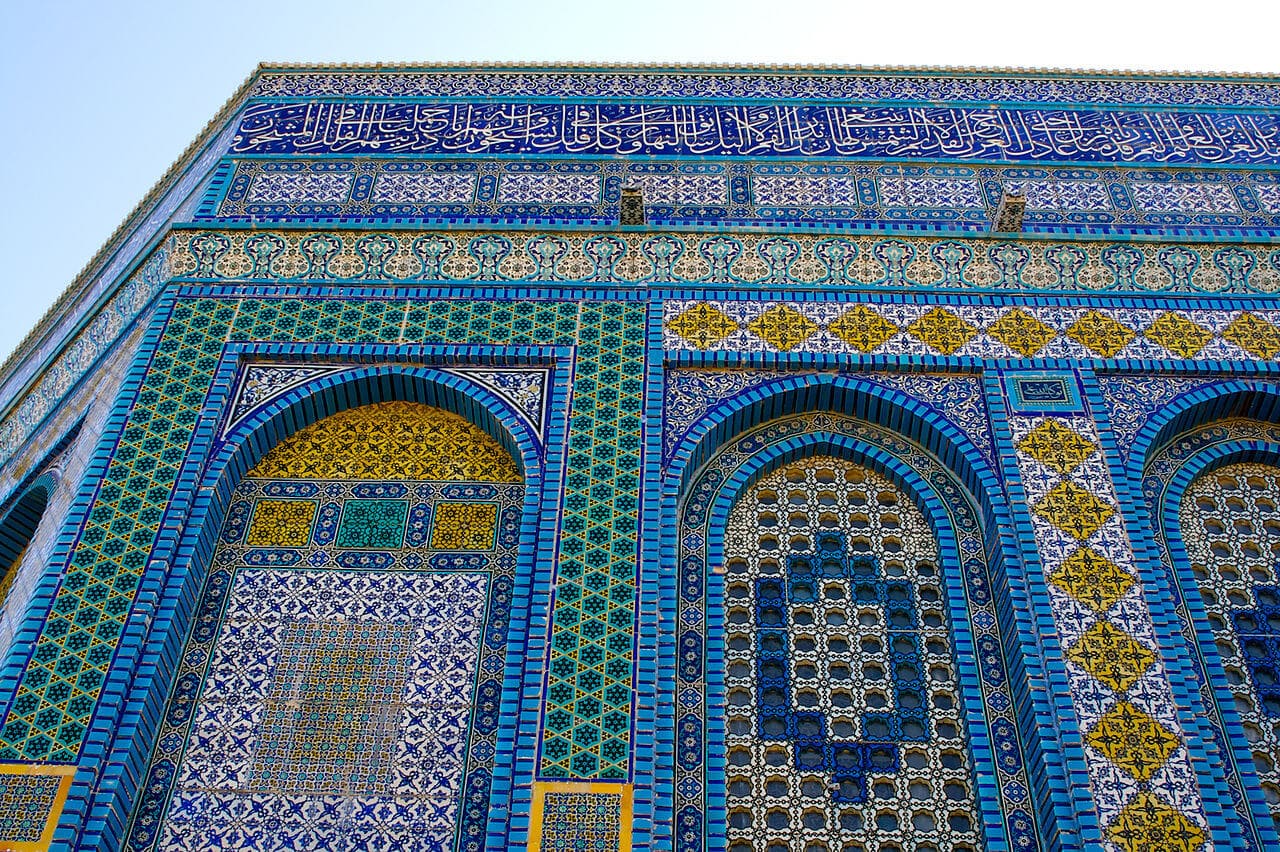

While calligraphy could serve as the dominant decoration for tile, it could also be combined with geometric patterns and arabesques, notably seen on the exterior of the Dome of the Rock, an Islamic shrine built on the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem.

Islamic Tile Techniques

Zellige Tile

“Zellige” (sometimes written as “zellij” or “zillij”) comes from the Arabic word “al zulaycha,” meaning “little polished stone.” Zellige tiles are multicolored mosaics, usually featuring complex geometric patterns.

To create zelliges, artisans would have first glazed the tiles on one side. They would then cut the tiles by drawing the geometric pattern onto the glazed tile, cutting out the form using a sharp hammer, and then bevelling the edges of the cut tile with a small hammer.

The next step was to prepare a drawing of how the different tile shapes and colors would be assembled. The cut tiles were assembled face-down on the floor according to the drawing, as close to one another as possible, and a mortar was poured over them. After the mortar had set, the resulting zellige could be installed.

The Turkish Cultural Foundation explains that zellige tile was often used for walls, vaults, mihrab niches, transitions to domes, and the interiors of domes.

The use of zellige mosaics originated in Morocco in the 10th century, using white and brown tones and imitating Roman mosaics. Succeeding dynasties continued to enrich the zellige design, and zellige was particularly popular during the Berber Dynasty in the 12th and 13th centuries. Later on, zellige tile would lend to the creation of Portugal’s azulejo tile.

Luster Painting

Luster painting is a complex painting and firing technique that suspends silver and copper oxides on the surface of a glazed tile. These metals refract the light and create what we see as a glossy appearance.

The luster painting technique was originally used on glass in Egypt and Syria in the eighth century, but was soon thereafter introduced to ceramics in Baghdad. Lusterware ceramics were then made almost exclusively in Baghdad for more than a century.

Although luster painting could work with multiple colors, we see more monochromatic examples that later spread elsewhere in Western Asia and then further west to North Africa, Europe, and America.

Underglaze Tile Painting

While luster painting involves painting on a glazed surface, underglaze painting is painted on unglazed tiles, according to Ensar Taçyildiz of the Ceramic Arts Network. The tile is bisque-fired and then painted with an underglaze. After painting the tiles, artisans apply a clear glaze and then fire them a final time.

Examples of underglaze-painted ceramics dating from the ninth century suggest that the technique itself is at least this old.

The Turkish Cultural Foundation explains that the colors originally used for underglaze painting included turquoise, violet, cobalt blue, green, and black. To prevent the colors from being dissolved by the glaze, artisans developed special pigments that had a similar composition to the clay slip. This combination created a strong bond that wouldn’t dissolve.

Cuerda Seca

The Met Museum describes the cuerda seca (Spanish for “dry cord”) technique as outlining areas of the tile that were to be painted with a greasy substance. These thin outlines kept different colors separated, leaving behind dry lines of unglazed tile.

According to Qantara, a site dedicated to Mediterranean heritage, cuerda seca is believed to have originated in the Middle East during the ninth century. Some cuerda seca techniques reached Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) as early as the second half of the 10th century, and the full cuerda seca method arrived in the 11th century. Cuerda seca flourished in Iran in the late 14th century, and was then introduced to Turkey and India, as well.

Whereas traditional cuerda seca techniques used substances made of animal fat and grease and mineral pigments such as manganese and iron, modern methods use mineral oil or wax resists.

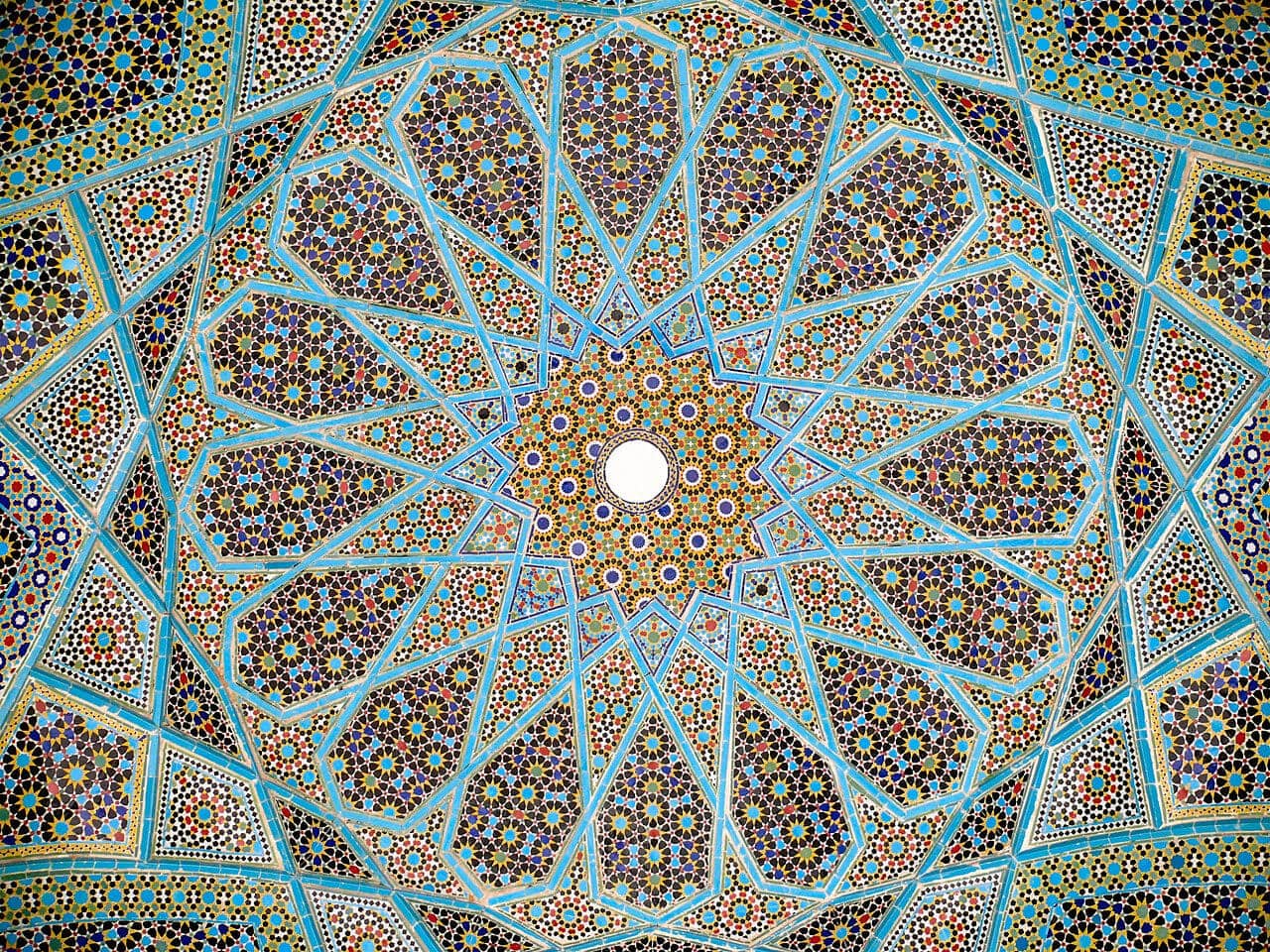

Haft Rang

The Iran Chamber Society records the haft rang (or “seven colors”) tile technique as becoming popular in Islamic architecture during the Safavid Empire (1502-1736), when many religious buildings were constructed. Haft rang tile was a good choice for economic reasons (it was both cheaper and quicker to produce), and the seven colors gave more artistic freedom to artisans. These colors usually included white, black, turquoise, ultramarine, yellow, red, and fawn, according to Iran Destination.

To create haft rang tile, artisans arranged square tiles next to each other, painted a design onto them in glazed colors, fired the tiles, and then arranged them next to each other once more during the installation to recreate the design.

Girih Tiles

In the article “Islamic Girih Tiles in Their Own Right as a History Lesson and Design Exercise in the Classroom,” Robert Earl Dewar explains that girih tiles consisted of tile patterns that formed five shapes/templates — bowtie, elongated hexagon, rhombus, pentagon, and decagon. These shapes, theorized Dewar, may have helped artisans design precise and complex large-scale geometric installations.

Although evidence suggests that girih tile methodology has been in use since around the year 1200, the expertise of these designs began to increase significantly in 1453 with the construction of the Darb-i Imam Shrine.

Islamic Tile’s Lasting Impact: Mathematics & Style

In 2007, physicists from Harvard and Princeton discovered that 15th-century Islamic girih tiles formed Penrose geometric patterns, a tessellated tiling system that wasn’t discovered in the West until the 1970s. British mathematical physicist Roger Penrose showed in 1973 that rhombus-shaped tiles could create a nonrepetitive pattern with five-fold rotational symmetry. These patterns were later found in metal alloys called quasi-crystals in 1984, changing our understanding of atomic packing.

These geometric designs that fit together much like pieces of a puzzle offered a surprising amount of creativity within a two-dimensional pattern repetition or “tessellation.” According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “[c]eramic tiles provided a perfect material for creating tessellated patterns that could cover entire walls or even buildings,” as the patterns formed units that could be infinitely expandable.

Historical Islamic tile incorporated mathematical savvy and design sensibility to create awe-inspiring tile, and its influence is evident in many modern applications. Individual tiles that present different patterns depending on the layout, patterned tiles that integrate on a larger surface, mosaics, and even the mix of geometric designs on individual tiles remind us of the creative possibilities with repetitive patterns and arrangements developed by Islamic artisans. Explore our Design Gallery for some contemporary Islamic-inspired tile examples we recognize today.